The Crisis in Our Pipes: Lead in Drinking Water

Parsippany. Trenton. Englewood Hospital. These are just the latest communities in New Jersey to show signs of the statewide crisis in drinking water infrastructure.

In search of solutions, co-chairs Sen. Linda Greenstein and Asm. John McKeon have re-convened the Joint Legislative Task Force on Drinking Water Infrastructure, which first met in November 2016. This hearing focused on the issue of lead in drinking water.

Sen. Greenstein opened by describing the urgency of the issue, and recent disruptions to clean water across the state. Asm. McKeon described how the massive and ongoing crisis in Flint, Michigan, first turned national attention to the issue of lead in drinking water, but that New Jersey’s critical infrastructure for fresh water and drinking water are at risk as well. In her remarks, Sen. Greenstein commended the work of New Jersey Future and Jersey Water Works in making water infrastructure a public issue and convening more than 100 key stakeholders. Sen. Christopher Bateman, Asw. Elizabeth Muoio, and Asm. John DiMaio also participated in the task force meeting.

Twenty-one School Districts Report Lead in Drinking Water So Far

On the issue of lead in school drinking water facilities, Robert Bumpus, assistant commissioner of the Division of Field Services, and Jim Palmer, executive director of project management at the New Jersey Department of Education, described its current initiative to require and fund school districts to conduct water testing for lead. To date, half of the regulated school districts (which cover 2,500 public schools, early childhood centers, and private schools for students with disabilities) have submitted results from lead testing. Of these, 21 districts have submitted results that indicate lead levels considered unsafe. (More are expected; a 2016 New Jersey Future study found reports from 49 school districts that had at least one instance of a tap that dispensed water with lead.) Asw. Muoio inquired about solutions for school districts, noting Camden City public schools’ use of bottled water for the past 14 years. So far, districts with high lead levels in drinking water have notified parents and staff and taken action to remediate or shut down affected taps, but these efforts are not currently funded by NJDOE.

Several environmental and public health groups focused on the devastating impacts of lead on the body, especially for children. Both Bruce Ruck, director of the New Jersey Poison Information and Education Center at Rutgers University, and the Education Law Center, drawing on lessons from a recent conference organized by Isles Institute at Princeton University entitled The Impact of Lead Exposure on Our Students, described some of the effects of lead poisoning on children’s learning capacity and educational outcomes: deficits in speech, language, hearing, memory, visual-spatial skills, attention, social behavior, and motor skills. He urged proactive monitoring and preventative measures for lead poisoning, so that “the child is not the lead detector.”

Doug O’Malley, director of the advocacy organization Environment New Jersey*, reiterated that the crisis of lead in drinking water “affects all communities—urban, suburban, and rural.” David Pringle, campaign director for Clean Water Action*, emphasized the need for urgency and creativity in funding, and Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, proposed several ideas for water infrastructure funding opportunities, such as using savings from preventing water leaks to pay for pipe replacements. Tittel stressed the immediate need for action due to the Trump administration’s freezing of EPA grant funding for critical environmental resources, including safe drinking water.

New State Funding, Technical Assistance Programs Promote Safe Drinking Water

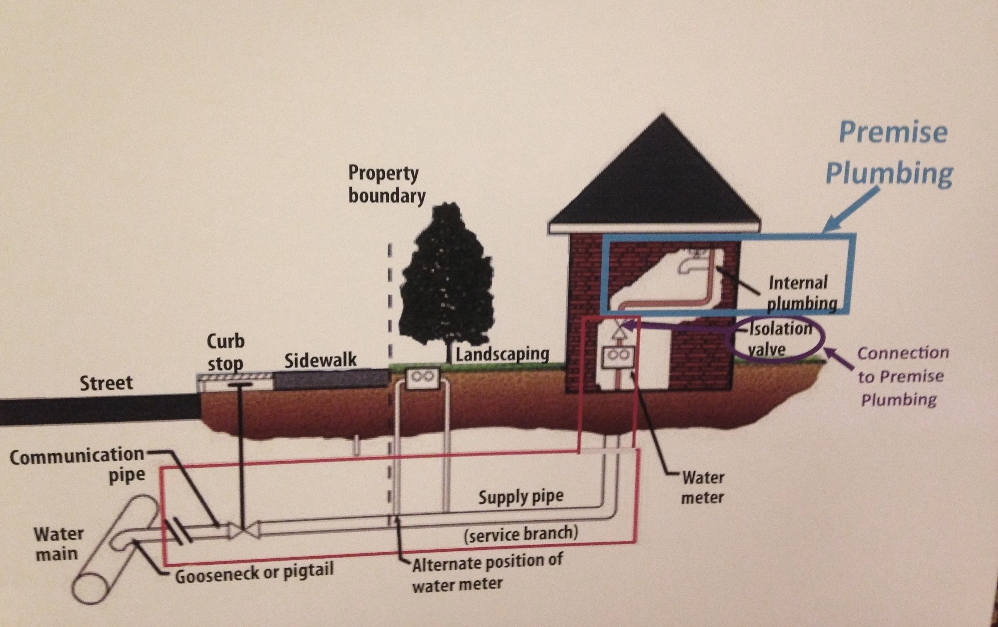

Dan Kennedy, assistant commissioner for of water resource management at the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection**, explained the jurisdictional issues with addressing lead in water. The NJDEP’s analyses of water systems show that lead is not present in the water mains, but occurs in service lines and within buildings. However, the agency’s authority to regulate conditions stops at the water meter, and funding that goes to water purveyors can only be used on pipes outside the property line. This makes it more difficult to fix the problem because often the lead contamination occurs inside the house or in the privately-owned service line, not at the regulated source.

Kennedy described steps that NJDEP has taken to address lead contamination. Prior to the Flint water crisis, the agency began a self-assessment. In 2016, it created a lead team and has implemented a work plan to strengthen regulations, provide technical assistance, and educate the public through the Lead in Drinking Water section of its website. The agency has also collaborated with NJDOE and worked with homeowners and schools to improve testing and training on how to minimize the risks of exposure to lead-tainted water.

David Zimmer of the New Jersey Environmental Infrastructure Trust (NJEIT)** described funding programs for municipalities and utilities that need to remediate lead contamination. It has instituted a new $30 million financing program to provide lower-income communities with zero-interest loans and 90 percent principal forgiveness to fund community projects to remediate lead in drinking water.

The legislative task force will be turning its attention to solutions this spring, as it works to meet its mandate to issue recommendations related to drinking water infrastructure.

Jersey Water Works is working to transform New Jersey’s inadequate water infrastructure through sustainable, cost-effective solutions that provide communities with clean water and waterways; healthier, safer neighborhoods; local jobs; flood and climate resilience; and economic growth. Check out Jersey Water Works’ Lead in Drinking Water resource page.

**Jersey Water Works Steering committee member

* Jersey Water Works member