Controlling Drinking Water Loss: What Can We Learn From Jersey WaterCheck?

In the early morning hours of Thursday, Aug. 19, 2021, a water main burst under West Front Street in Middletown, New Jersey. This “major” water main break continued to worsen throughout the day. Police reported to the scene. A sinkhole developed in the road that was so massive it swallowed a car, and traffic had to be diverted to other routes. About 90 homes in the immediate area were without water service. This type of spectacular water infrastructure failure with dramatic photos of automobiles sticking out of large holes in the street makes for a great news story, but it is thankfully a rare occurrence. However, every day water utilities here in New Jersey and around the country experience smaller leaks and other water losses that don’t make the nightly news but do cost systems thousands or even millions of dollars in unnecessary expenses and lost revenue. Newly updated data on Jersey WaterCheck help us measure how well utilities in New Jersey are controlling water loss.

Water loss, or more appropriately “non-revenue water,” refers to the difference between the amount of water treated by a utility and the amount actually billed to its customers. There are several reasons why these two numbers may be different, including:

- Water is exiting the treatment and distribution system before it reaches customers (e.g., there is a leaking water main or a tank that is overflowing)

- The customer’s meter is inaccurate—meters tend to slow down and under-read as they get older; and

- Certain customers are allowed to use water without paying for it, such as fire departments using water from hydrants to put out fires.

Water loss is both inevitable and expected for all water systems—even the most effectively managed system will have leaks—but it is a best practice to limit water loss to the greatest extent possible, whatever the cause. Every gallon of water that is treated but leaks into the ground before reaching a customer wastes money on treatment chemicals, electricity to pump water, and staff time, not to mention the potential damage to streets, the cost of involving police or other first responders, and the inconvenience to customers and commuters. Every gallon of water that isn’t read properly by a customer’s meter is a gallon not billed, which lowers the revenue utilities rely on to maintain the system today and into the future. Ultimately, water customers will face higher bills, which could lead to affordability concerns. And, if water loss is severe enough, it can impact a utility’s ability to provide safe and reliable drinking water.

How well are utilities in New Jersey controlling water loss? One important source of data to answer this question is Jersey WaterCheck. Jersey WaterCheck was created by Jersey Water Works (JWW) to tell the story of our state’s water and wastewater infrastructure needs. One of JWW’s shared goals is Effective and Financially Sustainable Systems, and under the subgoal Maintaining Systems, Jersey WaterCheck has the measure “Percentage of treated drinking water sent out for distribution that is not billed to customers (system-level).” The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) requires utilities to report this information on an annual basis.

In 2019, 179 water utilities reported a median percentage of treated water that is not billed of 13%. In 2020, 176 water utilities reported a median percentage of 11.7%. Most of the utilities reporting this data are either large utilities that serve more than 11,000 people or medium utilities that serve between 3,000 and 11,000 people. Small utilities serving under 3,000 people are under-reported in these numbers.

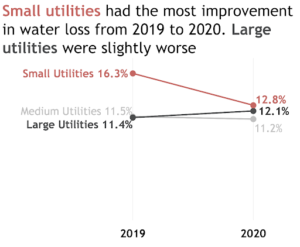

Even though the overall median percentage of treated water that is not billed decreased from 2019 to 2020, that was not true across all utility sizes. Small utilities that reported figures for both years saw the most improvement, whilst large utilities saw a slightly higher percentage in 2020 than they did in 2019.

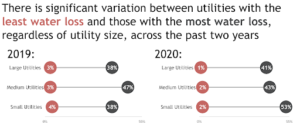

These figures represent the only median value—the middle value if you were to line up all of the water loss figures from lowest to highest. But the range of water loss percentages—the lowest and highest numbers—is quite dramatic across all utility sizes. The utilities with the lowest water loss report that just a few percent of treated gallons are not billed to customers. The utilities with the highest water loss, however, report that about one-third to one-half of treated gallons are not billed to customers. This range is evident in both 2019 and 2020 data.

At a very basic level, this data can help us understand whether a utility has a problem with treating far more water than customers pay for, but the percentage of treated water that is not billed is an outdated metric that is no longer used by water loss experts.

The percentage of treated water that is not billed cannot provide any insight into why the discrepancy exists or what the utility should do to fix the problem. If the discrepancy exists because there are numerous leaks in the pipe network, the utility should identify where leaks are occurring and replace failing transmission mains. If the discrepancy exists because meters are old and not properly recording the volume of water passing through them, however, utilities should leave their pipes alone and instead invest money in new meters.

Today, the industry standard for measuring water loss is the audit methodology developed by the American Water Works Association (AWWA) and the International Water Association (IWA). Their audit method goes deeper than the general number reported in New Jersey to better understand the root causes of the discrepancy, giving utilities information upon which they can act. In fact, the latest methodology does not involve calculating the percentage of treated water that is not billed at all, because the number is seen as misleading. AWWA and IWA offer utilities a free Water Audit Software tool for download in Excel that corresponds to their methodology, and there are many guidance documents and resources to help utilities complete the audit. Small utilities serving 10,000 or fewer people can get free technical assistance to complete water audits from groups funded through federal grants, including RCAP Solutions, the Environmental Finance Center Network, and the New Jersey Water Association.

Some states require all water utilities to complete annual water audits using the AWWA/IWA methodology. In New Jersey, only water utilities that fall within the jurisdiction of the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC) are required to complete full audits currently, and utilities will report on the number of line breaks per mile per year, a component of water audits, as part of the 2022 revised Water Quality Accountability Act (WQAA) requirements. But any utility would benefit from completing a water audit and using the results to prioritize capital projects. This is the best way that utilities can maximize their revenue, lower their costs, and limit the possibility of having their own major water main breaks end up on the evening news.